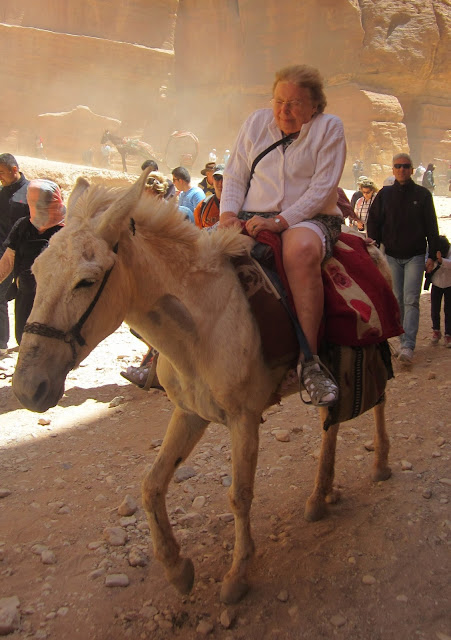

Today we went to Petra with some friends who are visiting us. However, since we've been there six or seven times, I didn't take any pictures of the city meticulously carved into the sides of the mountains, or its beautiful natural surroundings. There were a ton of tourists there, though--far, far more than I had ever seen before--so instead I snapped pictures of them, the people of Petra. A lot of strangers have taken my picture over the years here, so today, I decided it was time for me to do the same.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

Sunday, April 14, 2013

The Qur'an: Arrangement and Structure

A couple months ago we posted an entry on the basic definition of the Qur'an, which you can read by clicking here. Below is a follow-up to that post, on the arrangement and structure of the Qur'an. At some point, there will be two or three more, dealing with other issues related to the Qur'an.

As defined in the previous post on the Qur'an, Muslims believe that the Qur’an is the written record of

revelations from God given orally to the Prophet Muhammad by the angel Gabriel over a period

of about 23 years. These revelations are

divided in the Qur’an into 114 separate units, called Surahs, ranging in length

from 3 to 286 verses, called ayas. According

to the famous Persian Qur'anic commentator and historian Al-Tabari (838-923), the word Surah, which in English is translated as chapter, can

come from two sources. First is from the

root suur (سور), which means to enclose, fence in, wall in

or surround with a railing or wall. It

is from this root that the word for the type of wall that surrounds a home or a town—like that which

surrounds the old cities of Damascus or Jerusalem —comes, separating what

is inside from what is out. It is like

“the wall of a town,” he says, “meaning

the wall which encircles it, because of its elevation over what it surrounds.” Also, al-Tabari said Surah could come from

the root sa'er (سئر), which means to remain or be

left. It is from this root that the word suu'ra (سؤرة) comes, meaning that which is leftover.

Those who read the word this way, he says, define surah as “the part

which is left in the Qur’an over the rest of it, and which is retained." Or, in the words of the 20th century Lebanese scholar Mahmoud Ayoub, “the better

portion of a thing or separate sections, that is, a chapter.” Either way, a clear separation between

readings and into different units is denoted.

“Thus the word signifies a distinct section of the Qur’an separated from

what is before and after it,” says Ayoub. Regarding the word aya (آية), although translated into English as verse, it refers to that which

points to something else, or sign. In fact, besides this particular use of the word aya, the

Qur’an spends a great deal of time referring to the signs of God in nature

and the world. For example, Surah 42:29

says, “and of His signs (ayat) is the creation of the heavens and the earth and what

He has spread forth in both of them of living beings.”

Except for the opening surah, the surahs in the Qur'an are

ordered roughly—but not exactly—by length, from the longest to

the shortest. Each surah has a name—such

as The Criterion (25), The Pilgrimage (22), The Iron (57) and The Cow (2)—which comes from a prominent word or theme in the Surah. Sometimes, though, the name comes from a word

or theme that actually is not so prominent, as in the case of The Poets (26), which is 227 verses long, and the poets from which the surah gets its name

are not mentioned until verse 224. There

are also several Surahs that simply begin with certain individual Arabic letters and are given names that coincide with these letters. Muslims know the Surahs by these names, not

their numbers. Muhammad spent time in the cities of both Mecca and Medina, and each Surah is explained as

either having been from Muhammad’s Meccan or Medinan period, even though some

Meccan Surahs include ayas said to have been revealed in Medina , and vice versa. Generally, Meccan surahs are believed to be

those that are shorter in length—especially those near the end of the

Qur’an—and that speak more about broad themes, such as judgment, warning,

heaven and hell, belief in God and God’s signs, whereas the Medinan surahs are

believed to be of the longer variety and include more specific items regarding

rules, regulations and legislation. Finally,

except for The Repentance (9), each surah begins with the words, “in the name of God, the most Gracious, the most Merciful.”

And what about the material contained within these

surahs? What is the content of the

Qur’an? Without getting into too much

detail here, according to Egyptian-born professor of Islamic Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London, Muhammad Abdel

Haleem, "quantitatively speaking, the Qur’an consists of the various beliefs of

Islam by far, followed by moral issues, ritual aspects, and then legal

provisions." According to Ayoub, “The

Qur’an, broadly speaking, consists of moral and legal precepts, commands and

prohibitions with regard to lawful (halal) and unlawful (haram) actions,

promise (wa’d) of paradise for the pious and threat (wa’id) of punishment in

hell for the wicked. It also contains

reports of bygone prophets and their peoples, parables, similes and metaphors,

and admonitions. Finally, it sets forth

for the pious obligations (fara’id) of prayer, fasting, almsgiving, the rites

of pilgrimage, and struggle (jihad) in the way of God.”

It is important to know, though, that the Qur’an is not

laid out in a neat, orderly fashion, with, for example, beliefs in one section,

stories of ancient prophets in another, and ritual aspects and legal provisions

in other sections. The Qur’an is not

arranged in the form of a narrative, like the biblical books of Genesis or Exodus, or

like the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. In fact, just one Surah—Yusef/Surah 12,

which deals with the same Joseph (called Yusef in Arabic) from the book of Genesis—can really be

considered to be in story form. Its contents

are not arranged chronologically, or by theme or subject matter. Instead, many Surahs in fact have several

subjects, and may switch rapidly back and forth several times between subjects,

themes and/or stories involving various prophets, people and past events along with events contemporary to Muhammad. “The Qur’an is not like a legal

textbook that treats each subject in a separate chapter,” says Abdul

Haleem. “It may deal with matters of

belief, morals, ritual and legislation within one and the same Surah.”

This aspect of the Qur’an’s arrangement has been the

cause of much criticism from non-Arabic speaking—especially Western—readers of

the Qur’an. To such people, the quick

fluctuation between stories and themes makes the Qur’an seem disjointed and

haphazardly put together, and difficult to read. However, Muslims would argue that this

mingling of themes, characters and other aspects emphasizes their

interconnectedness. Also, the mixing

together of various ritual and legislative aspects with ideas about God,

doctrine and other religious beliefs ties everything back to God. “This gives its teachings more power and

persuasion, since they are all based on the belief in God and reinforced by

belief in the final judgment,” says Abdel Haleem.

For example, legal aspects, according to Abdel Haleem, “are

given more force through being related to beliefs, rituals and morals.” To highlight this idea he points to verse 255

in Surah al-Baqara (2), which is a lengthy description of God and God’s

attributes that is preceded by an admonition to give charitably. Also, he points to a section in the same

Surah that deals with divorce, but is broken up at some point by a reminder to

be devoted to prayer. Such mixing is

purposeful, providing for a constant reminder of the various themes and issues

found in the Qur’an. If the Qur’an

followed a more neat thematic, chronological or historical arrangement, he

said, “it would not have had the powerful effect it does by using these themes

to reinforce its message in various places.”

Wednesday, April 03, 2013

No, I Don't Like Your Hair

Before we came to Jordan seven years ago some people suggested I cut my hair. You know, to fit in better, so people in this conservative society wouldn't be turned off by my long locks. Anyway, I didn't cut it, and I've never had any problem. Sure, I get a few more stares than the average white guy here, but I did back at home too, especially from the occasional anxious store clerk who is certain I look like a shoplifter. I've never gotten the sense that people wouldn't talk to me or distrusted me here because I looked different. I have friends young and old, and with varying degrees of religiosity, and the strangers I meet every day are perfectly willing to talk to me. My long hair, though, does set me apart aesthetically from nearly everyone in Jordan. That is true. Because of that, I am every so often forced to answer questions about it, usually from a kid. Such an inquisition took place yesterday, while I was innocently waiting for my shawarma. My inquisitor was around twelve or thirteen years old, and he took a keen interest in how I looked while waiting for his shawarma too. The following is the English translation of our conversation.

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why not?

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why not? Why is your hair like that?

Pause, confusion.

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why is your hair like that? It's too short.

Kid: What?

Me: It's too short.

Pause, again.

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why? You don't like it?

Kid: No.

Me: What? Is it prohibited?

Kid: Yes.

I smiled wide, and laughed, and began to consider my next response. But, alas, his shawarma was ready, and he grabbed it and walked away, leaving me alone, with my forbidden hair.

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why not?

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why not? Why is your hair like that?

Pause, confusion.

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why is your hair like that? It's too short.

Kid: What?

Me: It's too short.

Pause, again.

Kid: Why is your hair like that?

Me: Why? You don't like it?

Kid: No.

Me: What? Is it prohibited?

Kid: Yes.

I smiled wide, and laughed, and began to consider my next response. But, alas, his shawarma was ready, and he grabbed it and walked away, leaving me alone, with my forbidden hair.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)